|

| |

Considered lost for decades, John

Barry's first symphonic concert is back on CD. Read

an interview with the 007 composer on this historic

find...

|

|

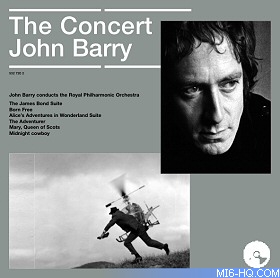

The Concert: John Barry

11th May 2010

|

Back in 1972, a studio recording was made

of the concert John Barry conducted

at The Royal Albert Hall, the first

symphonic concert of his career. Comprised of his work

on six James Bond films to date, the Bond Suite lasts for

almost 18 minutes and runs from "Dr.

No" to "Diamonds

Are Forever", released just one year previous.

Along with

renditions of his critically acclaimed work "Born

Free" and "Midnight Cowboy", the master

tapes of this historic concert recorded by Polydor UK were

long considered lost, until Stéphane Lerouge found

them in the archives of Universal Japan!

Almost forty years on from its original

recording, "The

Concert: John Barry" has been re-released this week

(10th May 2010) by Universal Music France. The new CD includes

a 16 page booklet featuring a new interview with Barry

and stills provided by EON Productions. |

|

Above: New CD cover artwork

Amazon

France Amazon

France

Amazon

USA Amazon

USA

|

MI6 readers can now enjoy the John Barry

interview conducted by film music specialist Stéphane

Lerouge for this release:

"Ever since I was a child I've considered poetry and music

to be two twin sisters, completely inseparable. Over the years

I've always tried to develop a poetic universe of my own, not

only for filmmakers but, through their films, for audiences too.

I work with very precise harmonic mechanisms to do this... and

my melodies take shape according to what these mechanisms are.

Sometimes the melodies weave together straight away; at times

they have to be guided and adjusted. But, whatever happens, they

always find a kind of foster parent with my harmonies. In my

work, the horizontal comes from the vertical."

|

|

|

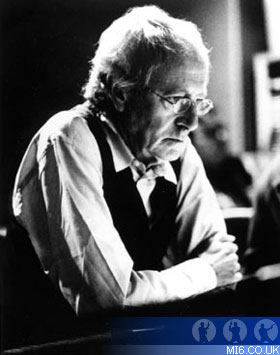

British composer John Barry was referring to one of his

singularities: his unconventional approach to harmony.

This particularity of his immediately struck attentive

listeners at the dawn of the Sixties, as soon as they discovered

the music he'd written for his first films; a whole series

of box-office successes quickly followed, films thanks

to which he suddenly found himself thrust to the top as

a composer for young moderns: Born Free and The Knack,

a film that was a manifesto for Swinging London, the first

James Bonds, and then the Bond anti-hero named Harry Palmer,

who was played by Michael Caine.

Millions of cinema-goers

and music-lovers discovered the singular splendour of

John Barry's compositions for the screen: harmonic traps;

a

highly personal sense of lyricism and melody which immediately

hooked people's memories; a taste for characteristic,

unusual timbres; a desire to create surprise with the instruments

he chose... Barry walked a tightrope between the spectacular

and the cinema d'auteur. |

He is a sophisticated composer whose most visible works, the

most famous, did little to conceal a more secret vein that was

more melancholy, a vein that leaned towards introspection.

In 1972, John Barry was thirty-nine and had

just written three works, each with a different aesthetic, that

were destined

to leave an indelible stamp on the collective memory: the historical

production Mary, Queen of Scots, the James Bond film Diamonds

are Forever and his theme-music for The Persuaders. And then

Sydney Samuelson invited him to conduct the orchestra at the

third Filmharmonic concert in London. Organized as an annual

charity event, the Filmharmonic was to see a procession of

guest-conductors take up the baton: such prestigious musicians

as Henry Mancini, Elmer Bernstein, and soon Francis Lai. In

accepting Samuelson's offer, Barry was well aware of what was

at stake, if not the symbolic reach of such an offer: it would

be his first symphonic concert, and the venue was to be the

legendary Royal Albert Hall.

Miklos Rozsa, the great "Wagnerian

gypsy" in the old days of Hollywood, was to conductor

the first part of the concert, with Barry replacing him after

the intermission; it was a programme where Ben Hur extended

a hand to the spy known as 007. The division between the conductors'

roles was crystal-clear: Barry represented the present, while

Rozsa was the musical memory of films, its heritage. "I

was very impressed and quite moved to find myself facing a

legend like Rozsa," confesses John Barry today. "He

was precise and very clear, both as a composer and as a conductor.

He'd begun writing for the screen at the beginning of the talkies

in the Thirties, while I was still a little boy. In my father's

cinemas in Yorkshire, his scores for The Thief of Bagdad or

The Jungle Book were things of my dreams. Rozsa belonged to

the galaxy of composers who shaped my vocation. And then thirty

years later, there we were, sharing the same stage and the

same orchestra." Between the two halves of the concert,

it wasn't merely one conductor handing over to the second:

the baton was also clearly figurative, a transition between

the old and new worlds.

In 1962, John Barry was still fronting his John Barry Seven,

a group influenced by Bill Haley and Little Richard. Ten years

later he was at The Royal Albert Hall in tails, conducting The

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The concert was aired later on

the BBC during a special evening entitled John Barry and His

Music. It was more than a concert; it was a diploma that recognized

his professional ascension, almost a coronation. The trumpeter

who played with The John Barry Seven had become a young world-leader

in film-music; more than that, he had breathed new life into

it.

|

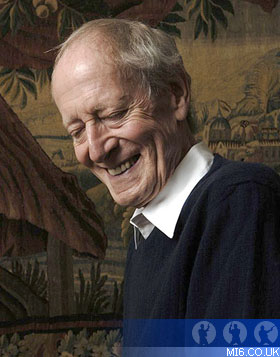

"It's true," he says today. "That

concert was a milestone in the evolution of my career in

more than one respect. That being said, I wasn't very confident:

I was going to conduct a symphony orchestra in front of

an audience for the first time. I prefer to stay in the

shadows, and the spotlight makes me feel uncomfortable.

Sammy Davis Jr. often said to me, 'Performing in front

of spectators is like being an addict: when I'm off the

stage I have withdrawal symptoms!' It was the same with

my friend Henry Mancini; he loved conducting his film-music

at concerts. For me, on the other hand, it's hell... I

don't like exposing myself in public. I take pleasure in

isolation: I like the solitude, with just a sheet of blank

music-paper in front of me; or else in the studios, where

things I've imagined on paper come to life thanks to the

musicians. There's a dimension that fascinates me in the

process of creation, particularly composing and recording...

a mysterious one that belongs to something intimate, inexplicable.

It's a dimension that partly escapes the creator. For all

those reasons, it took a violent effort for me to go onstage

at The Royal Albert Hall. But it had its rewards: the audience

was incredibly enthusiastic and receptive. Once the concert

was over, I had a smile on my face again." |

|

|

One has to give credit to the composer for submitting

his scores to a vigorous overhaul, given the Royal Philharmonic's

instrumental

line-up. Barry had to rethink the orchestration of certain works

due to the absence of a rhythm section, and also key instruments

such as the Moog used in the film On

Her Majesty’s Secret

Service, the cimbalom in The Persuaders or The Adventurer, or

else the harmonica in Midnight Cowboy. "It would have been

frustrating to ask Toots Thielemans to come in just for one piece," he

concedes. "I had a full orchestra at my disposal, so it

was up to me to adapt. At a pinch, you could say it was a game,

a rather stimulating exercise. I managed to compensate for the

absence of some of the soloists by making full use of the orchestra's

resources. I had a trumpet play the main role in Midnight Cowboy,

for example: it's still the same piece, but the change of instrument

causes the music to take on a different character."

"Some of his

most performed pieces are here but when scored specially

for the Royal

Philharmonic Orchestra, another dimension is added. The

James Bond Suite takes on a new size and I am sure will

be regarded as a work of major importance. If Bond is

007, Barry is 008." - Lyricist Don Black on the

original sleeve notes.

|

One

of the high points in the concert was a shattering James Bond

Suite that lasted seventeen minutes, a kind of musical compression

of the first seven Bond films, from Doctor No to the film Diamonds

are Forever, which had been released in cinemas the previous

year. "I tried to preserve the best of the Bonds, and write

a resume in a suite with a continuity that's fluid, logical and

natural," explains John Barry. "With hindsight, you

can see that this suite corresponds to the "classic" period

in the series, a period which ends with Diamonds, the last film

with Sean Connery. Obviously that period is my favourite, and

its template still remains Goldfinger, the Bond film where, in

terms of style, all the codes and references found their place:

the gun-sights, the opening sequence, the animated main-title,

Peter Hunt's editing... It was also the first Bond where I had

sole responsibility for the music; so I was able to assert a

compositional style inspired by what I learned from Bill Russo,

Stan Kenton's arranger: a particular way of adapting the brass

right across the register from the deepest bass to the highest

treble, with sharp attacks and incisive punches. That's where

you find the roots of the 'Bond sound'."

It was something

of a paradox that Barry created his Bond Suite just when he

was about to move on from 007: during the period featuring Roger

Moore, Barry went back to the Bond films intermittently, bidding

his final farewell to the series in 1987 with The

Living Daylights.

The first Timothy Dalton film was the last Barry. Years have

passed, but the James Bond Suite has stood the test of time:

even today, it invariably concludes the composer's concerts

throughout

Europe.

|

|

|

For the rest of his Filmharmonic concert, John Barry drew

up a subtle balance, with doses of music from the emblematic

soundtracks of the Sixties – Midnight Cowboy and

the Oscar-winning Born Free, a grandiose evocation of nature

and wide open spaces – and some recent works: the

theme-tune for the Adventurer television series (a more

serious face which had a more dramatic symphonic treatment),

the main theme from Mary, Queen of Scots (where the grace

of Erich Gruenberg's violin seems to make time stand still)

and, above all, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,

a new adaptation of the Lewis Carroll classic. With the British

release of Australian director William Sterling's film only

two months away, Barry unveiled its three central themes – three

ballads – as a seductive, seven-minute suite. Carroll's

subject took Barry's imagination – and also that of lyricist

Don Black – to a much higher level: their readings of

Alice translated not so much the picturesque in Carroll's universe,

but rather its serious, psychoanalytical dimension.

|

The Me

I Never Knew, especially, carried the composer's art to its

quintessence, with a sad lyricism and sinuous song-lines perverted

by abrasive harmonies. Barry was never bettered in the search

for a musical equivalent to the troubling tale written by Lewis

Carroll and its profound themes: traversing the mirror, and

the loss of innocence.

There were two consequences to the triumphant

welcome reserved by Filmharmonic 1972: first, John Barry returned

to the stage

of The Royal Albert Hall for the event's subsequent edition

a year later; and Barry also went to Abbey Road to record a

large part of the concert for Polydor, the record-label with

which he had just signed a contract as an artist. Released

towards the end of 1972, The Concert John Barry became the

first 33rpm LP produced under the new contract. It was never

reissued in its entirety, curiously, because the master-tapes

were reported missing. Providence, however, took a hand thirty-eight

years later when the tapes were located among the archives

of Universal Music in Japan. Today their discovery has resulted

in this CD reissue of a historic album, and the music is enhanced

by the addition of other John Barry classics from the Seventies:

first there are the Polydor versions of Walkabout and the 1970

western Monte Walsh, and they are completed by The Deep (which,

according to Barry, was "A terribly complicated film to

set to music: most of the action took place underwater"),

and The Day Of The Locust – a caustic pondering of the

dark side of Hollywood – which also marked the second

time the composer had worked with director John Schlesinger,

five years after Midnight Cowboy.

In many respects, The Concert

John Barry came as a milestone-recording in the composer's

career. For John Barry, it was an opportunity to take his film-music

to the concert-stage, like Prokofiev adapting the suites from

Lieutenant Kijé or Alexander Nevsky. It was also a means

of giving the public a synthesis of his first ten years in

films. Twenty years later, Barry would extend that approach

when he conducted the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra again for

two albums entitled Moviola. In the interval, his repertoire

had grown to include such gems as Somewhere In Time, Body Heat,

Frances, Out of Africa, Cotton Club and Dances with Wolves.

But above all, Barry's writing had grown fuller and matured;

an impression that was confirmed by his diptych The Beyondness

of Things/Eternal Echoes, composed at the turn of the 21st

century. The colours appear more autumnal, and his inspiration

is more elegiac, more introspective, too. As if, in the man

and the artist, the share of melancholy had definitively gained

the upper hand.

In the light of this evolution, revisiting

The Concert John Barry takes on extraordinary interest: "I've

rediscovered this album with emotion," concludes Barry

with a smile. "It's a look in the rear-view mirror, a

photograph of the way I was composing and conducting during

that period. Curiously enough, I was the first to be surprised

when I heard the sound of my music at a concert; it hadn't

been written with that in mind. Conceived for pictures, it

could exist perfectly well outside that context and lead its

own life in total autonomy. I'd hoped that this would be so

but, until then, I had no concrete evidence. That's the experience

I gained from this adventure: to me, it's the major impression

left by The Concert."

"The Concert: John Barry" was released in France

on 10th May 2010 by Universal Music France. The USA release will

follow on 18th May 2010 through 101 Distribution

Thanks to Stéphane Lerouge for his kind

permission to publish this interview.