His real name is Bond, Jack Bond

29-Jun-2008 • Bond News

In a discreet house on a quiet street in Fulham, west London, there lives an ageing beauty with a killer secret. In her hallway hang posters of Thunderball, and on the sofa sits a jolly little puppet of Sean Connery. The walls are lined with film books, and on her desk are two boxes of dusty files, court documents and scandalous letters in a 1960s typeface.

Like a latterday Ms Moneypenny, she holds the secrets of James Bond. Her name is Whittingham. Sylvan Whittingham.

Is she Ian Flemingâs daughter? God, no. Flemingâs name is anathema here. Her father was Jack Whittingham, a celebrated screenwriter of the 1950s and 1960s. It was Jack, she claims, who gave us Bond as we know him.

In 1959, Whittinghamâs father had been brought in by the film producer Kevin McClory to work on an original screenplay based on Flemingâs famous secret agent. (Fleming had had an earlier bash at writing his own, but forgot to put any action in it.)

The problem of how to film Bond had rumbled on for years. What passed for steely cool in the books would come off as charmless froideur on screen. But man-about-town Jack turned out to be the fire to Flemingâs ice. In a tobacco-stained study at his Surrey home, the dashing, hard-drinking ladiesâ man produced a thrilling tale called Thunderball. And he injected Flemingâs uptight gentleman spy with quippy humour, arch sexuality and plenty of action. Rather like Jack, in fact.

âI always say that Daddy was an honourable man,â says Whittingham, now 64, in a voice that seems to come courtesy of Diana Rigg. âExcept when it came to women, of course.â She smiles.

âBut he was a marvellous writer and theyâd had real trouble with Flemingâs novels. The violent, sadistic, colder, misogynistic Bond of the books didnât work on the big screen. The audience, back then, didnât want it. There was no humour, no charm. Daddy turned Bond into the suave hero they needed.â

In fact, Jack himself cut an altogether Bond-like swathe through the London scene. âBy the 1960s he was living the [Bond] fantasy,â she remembers. âHe bought himself a Jaguar XK140 and would take his women to Le Cirque, where James Bond used to gamble. They were very heady days, the beginning of the Sixties.â

This distinctly glamorous brand of adventure courses through the family blood. Sylvan was a 1960s pop star who co-wrote many classic songs, including Delilah. Even today the derring-do continues: Jackâs grandson, Sam, is officially the fastest recumbent cyclist on earth, having reached a speed of 81mph on his Diablo cycle in the Nevada desert.

If Jackâs legacy is holding up nicely in the family, itâs a very different story outside. In fact, his contribution to the making of Bond has been suspiciously underdocumented.

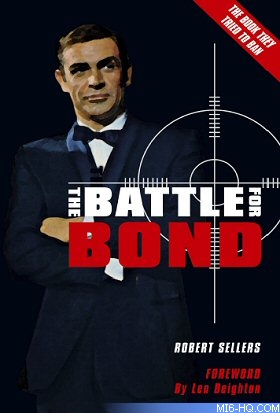

Last year a book called The Battle for Bond described Jackâs role in creating the movie icon â but the publisher was asked to pulp all the copies after Flemingâs heirs objected to the inclusion of various pieces of Flemingâs correspondence â which Sylvan Whittingham had provided. The publisher, however, has had his revenge â and has served it up with appropriate Bond-style sangfroid.

Len Deighton, author of The Ipcress File, was drafted in to write a foreword for the new edition of the book, which came out this month. In it he takes Flemingâs family to task for ignoble censorship. âHow Ian Fleming would have hated to know that this book had been censored . . . As a gentleman, he would have felt harassing a fellow author to be the ultimate demonstration of bad taste.â

A sweet gesture â but anyone who reads beyond the first chapter couldnât possibly agree with Deighton. Were Fleming alive today, itâs not hard to imagine what his response would be: hire Max Clifford to start a mud-slinging campaign and take a match to every last copy.

âI think he [Fleming] would have wanted the book squashed, yes,â Whittingham says cuttingly. âHe was naive, and he was arrogant. He felt my father had been paid for his screenplay. He felt he owned it.â The problem was plagiarism. After initial flurries of excitement over Jackâs Thunderball script â with dreams of Alfred Hitchcock as director and Richard Burton as Bond â both money and enthusiasm dried up. McClory, an Irishman, registered too high in the blarney stakes and too low in the social order for Flemingâs taste, and he was getting serious interest from other film men â notably Cubby Broccoli. Perhaps better to wait and get it right. The completed script was put on hold.

Then, Fleming repaired to Golden-eye â his Jamaican retreat â to write his annual Bond novel. Whether through hubris, naivety or pure exhaustion, he reached for Jackâs Thunderball script and began to type. A few weeks before publication in 1961, McClory got wind of Flemingâs new book. Both the producer and Jack attempted to have publication stopped, but Flemingâs publisher, Jonathan Cape, managed to get the novel temporarily passed by a judge.

âQuite ghastlyâ was Flemingâs view of his former colleague. âIâm sure Bond never had to go through anything like this.â

It took two years for the proper trial, which became a media circus, to make it to the High Court. In the interim, Fleming had suffered a stroke. Jack was also a hard-living 1960s writer and was â according to his daughter â âsomewhat impressedâ by Flemingâs drinking. âMy father was told by his doctor he wasnât to have any drink, but he pleaded, and the doctor said he could have one measure a day. Daddy went to great trouble to find the strongest drink in the world â green chartreuse,â she says, laughing.

Laughter was scarce by the time the trial came around: in the thick of proceedings, Fleming had two heart attacks. Jack Whittingham, who had terrible angina himself, took the stand to say that Fleming had barely contributed to the writing of the screenplay; furthermore, direct cribbing had been found on 200 pages of Flemingâs novel. Pushed by his backers, the Bond author settled.

Fleming had underestimated his foe. What he didnât know was that Jack had been toughened by a Bond-like life of fast cars and faster women. Born the son of a Yorkshire wool merchant, he had oozed confidence as a young man and made a splash with the ladies when he went up to Oxford.

âHe met Betty Offield there, heir to the Wrigleyâs gum fortune,â says Sylvan. âThey fell in love and she invited him over to America to stay. They used to go shark-fishing off her island in California. Later, he bought a solitaire diamond ring and went to Chicago to propose â but by the time he got there, sheâd fallen for somebody else.

âIn a bar, drowning his sorrows, he met a female gangster called Texas Guinan â a glamorous blonde â who took him on. She sent him all over town with deliveries for her, probably drugs. He became her pet for a while, before he sold the ring so he could afford to get home.â

After a stint in Iceland during the war â where he was permanently sloshed and would often fall down on parade â Jack returned to England and his wife, Margot, whom he had married in 1942. He was never faithful. âMy mother was stunningly beautiful, with a frightened-rabbit look in her eyes, which were violet. She was a lost soul: mental problems, breakdowns, depression,â Sylvan says.

It figures. At 50 â âa dangerous age for a manâ, she says â her father had a three-year affair with a 17-year-old called Roberta Hallbrook. âShe was very glamorous, a model who owned an ocelot coat. I couldnât work out why she wanted to be friends with me, but she was after my dad. He put her in a love nest in Basil Street [near Harrods], though he later tried to escape from her and moved to Malta. He wanted to make a fresh start but she pursued him. âThey used to meet in Capri. One day she arrived and said, âIâm not staying â Iâve just come to show you thisâ: a £10,000 engagement ring from Anthony Edgar, the H Samuel heir. âNow take me back to the airport,â she said.â

If Jack could handle the women, he could certainly handle Fleming. After the trial, the Bond author felt deeply humiliated; and he remained resentful for the rest of his life â believing he had caved in under undue pressure. Nor was that the end of the matter. As Jack had been the principal witness, rather than plaintiff, he was then able to sue for his own damages. But as the case crept to court, Fleming had another heart attack: he died in 1964.

âMy gosh, I remember when we heard,â says Sylvan. âWe were in Antibes, where Daddy kept a little boat, and it came on the news. There was a frozen moment of silence. Daddy just sat down and put his head in his hands. He was shattered. It was so complicated because, on a human level, he felt so guilty. He said, âWhat have I done?â â It was impossible to sue a dead man â so, on top of the guilt, Jack now faced astronomical legal costs. Then, outrageously, McClory knifed his âfriendâ in the back. Having promised to look after Jackâs future interests in Thunderball, he neglected to tell him that another version of the screenplay was being used for the eventual film â and that his name had been bumped well down the credits. In fact, Jack found out only when he saw the film at the cinema.

He died in 1972, but his daughter is determined people should know what her father did for Bond. It wasnât just that he crafted so much of the story for Thunderball; his lasting legacy is that he was the first man to crack how to translate book Bond into film Bond.

This take isnât unique to a devoted daughter. Andrew Lycett, the author of Ian Fleming: the Man Behind James Bond, says: âI think it is true to say that the Whittingham Bond did have a significant input on the later cinematic Bond.â

Famously, Fleming was not a great fan of the eventual screen incarnation of his 007 in Dr No and Thunderball. But so well versed was Jack in the sexual frisson that could come from a raised eyebrow or a well-delivered double entendre that he was better able to understand what passed for popcorn popularity than the elitist, Establishment-obsessed Fleming. Sylvan certainly believes so.

âDaddy was pivotal in taking the books into the film world. If he hadnât done such a good job, produced a character who was acceptable to a 1950s audience, Bond would have bombed and that would have been it. Thunderball was the one on which all the others were based; it gave the formula for what would succeed.â

For all their differences, Ian Fleming and Jack Whittingham also had certain traits in common. Both suffered from writerly insecurities and were prone to self-destructive excess. While on his deathbed, Jack was blowing smoke rings out of a hole in his throat; and Fleming had boozed on to the end.

Between them, they produced a film hero with Flemingâs icy heart and Jack Whittinghamâs easy charm who has captivated audiences for nearly 50 years. And that is how long it has taken for Jack to get the credit he deserves. âThatâs right,â says his daughter. âBut I like to think of it this way: never say never.â

The Battle for Bond by Robert Sellers, with a foreword by Len Deighton, is published by Tomahawk Press at £9.99.

Discuss this news here...

Discuss this news here...